MAHABHARAT

The Mahābhārata (/məˌhɑːˈbɑːrətə, ˌmɑːhə-/ mə-HAH-BAR-ə-tə, MAH-hə-;[1][2][3][4] Sanskrit: महाभारतम्, Mahābhāratam, pronounced [mɐɦaːˈbʱaːrɐt̪ɐm]) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India revered in Hinduism, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa.[5] It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kurukshetra War, a war of succession between two groups of princely cousins, the Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas.

| Mahabharata | |

|---|---|

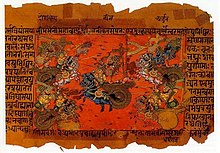

Manuscript illustration of the Battle of Kurukshetra |

It also contains philosophical and devotional material, such as a discussion of the four "goals of life" or puruṣārtha (12.161). Among the principal works and stories in the Mahābhārata are the Bhagavad Gita, the story of Damayanti, the story of Shakuntala, the story of Pururava and Urvashi, the story of Savitri and Satyavan, the story of Kacha and Devayani, the story of Rishyasringa and an abbreviated version of the Rāmāyaṇa, often considered as works in their own right.

Traditionally, the authorship of the Mahābhārata is attributed to Vyāsa. There have been many attempts to unravel its historical growth and compositional layers. The bulk of the Mahābhārata was probably compiled between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century CE, with the oldest preserved parts not much older than around 400 BCE.[6][7] The text probably reached its final form by the early Gupta period (c. 4th century CE).[8][9]

The Mahābhārata is the longest epic poem known and has been described as "the longest poem ever written".[10][11] Its longest version consists of over 100,000 śloka or over 200,000 individual verse lines (each shloka is a couplet), and long prose passages. At about 1.8 million words in total, the Mahābhārata is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, or about four times the length of the Rāmāyaṇa.[12][13] W. J. Johnson has compared the importance of the Mahābhārata in the context of world civilization to that of the Bible, the Quran, the works of Homer, Greek drama, or the works of William Shakespeare.[14] Within the Indian tradition it is sometimes called the fifth Veda.[15]

The title is translated as "Great Bharat (India)," or "the story of the great descendents of Bharata."[16][17]

Textual history and structure

The epic is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyāsa, who is also a major character in the epic. Vyāsa described it as being itihāsa (transl. history). He also describes the Guru–shishya tradition, which traces all great teachers and their students of the Vedic times.

The first section of the Mahābhārata states that it was Ganesha who wrote down the text to Vyasa's dictation, but this is regarded by scholars as a later interpolation to the epic and the "Critical Edition" doesn't include Ganesha at all.[18]

The epic employs the story within a story structure, otherwise known as frametales, popular in many Indian religious and non-religious works. It is first recited at Takshashila by the sage Vaiśampāyana,[19][20] a disciple of Vyāsa, to the King Janamejaya who was the great-grandson of the Pāṇḍava prince Arjuna. The story is then recited again by a professional storyteller named Ugraśrava Sauti, many years later, to an assemblage of sages performing the 12-year sacrifice for the king Saunaka Kulapati in the Naimiśa Forest.

The text was described by some early 20th-century Indologists as unstructured and chaotic. Hermann Oldenberg supposed that the original poem must once have carried an immense "tragic force" but dismissed the full text as a "horrible chaos."[21] Moritz Winternitz (Geschichte der indischen Literatur 1909) considered that "only unpoetical theologists and clumsy scribes" could have lumped the parts of disparate origin into an unordered whole.[22]

Accretion and redaction

Research on the Mahābhārata has put an enormous effort into recognizing and dating layers within the text. Some elements of the present Mahābhārata can be traced back to Vedic times.[23] The background to the Mahābhārata suggests the origin of the epic occurs "after the very early Vedic period" and before "the first Indian 'empire' was to rise in the third century B.C." That this is "a date not too far removed from the 8th or 9th century B.C."[7][24] is likely. Mahābhārata started as an orally-transmitted tale of the charioteer bards.[25] It is generally agreed that "Unlike the Vedas, which have to be preserved letter-perfect, the epic was a popular work whose reciters would inevitably conform to changes in language and style,"[24] so the earliest 'surviving' components of this dynamic text are believed to be no older than the earliest 'external' references we have to the epic, which include an reference in Panini's 4th century BCE grammar Aṣṭādhyāyī 4:2:56.[7][24] Vishnu Sukthankar, editor of the first great critical edition of the Mahābhārata, commented: "It is useless to think of reconstructing a fluid text in an original shape, based on an archetype and a stemma codicum. What then is possible? Our objective can only be to reconstruct the oldest form of the text which it is possible to reach based on the manuscript material available."[26] That manuscript evidence is somewhat late, given its material composition and the climate of India, but it is very extensive.

The Mahābhārata itself (1.1.61) distinguishes a core portion of 24,000 verses: the Bhārata proper, as opposed to additional secondary material, while the Aśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra (3.4.4) makes a similar distinction. At least three redactions of the text are commonly recognized: Jaya (Victory) with 8,800 verses attributed to Vyāsa, Bhārata with 24,000 verses as recited by Vaiśampāyana, and finally the Mahābhārata as recited by Ugraśrava Sauti with over 100,000 verses.[27][28] However, some scholars, such as John Brockington, argue that Jaya and Bharata refer to the same text, and ascribe the theory of Jaya with 8,800 verses to a misreading of a verse in Ādiparvan (1.1.81).[29] The redaction of this large body of text was carried out after formal principles, emphasizing the numbers 18[30] and 12. The addition of the latest parts may be dated by the absence of the Anuśāsana-Parva and the Virāta Parva from the "Spitzer manuscript".[31] The oldest surviving Sanskrit text dates to the Kushan Period (200 CE).[32]

According to what one character says at Mbh. 1.1.50, there were three versions of the epic, beginning with Manu (1.1.27), Astika (1.3, sub-Parva 5), or Vasu (1.57), respectively. These versions would correspond to the addition of one and then another 'frame' settings of dialogues. The Vasu version would omit the frame settings and begin with the account of the birth of Vyasa. The astika version would add the sarpasattra and aśvamedha material from Brahmanical literature, introduce the name Mahābhārata, and identify Vyāsa as the work's author. The redactors of these additions were probably Pāñcarātrin scholars who according to Oberlies (1998) likely retained control over the text until its final redaction. Mention of the Huna in the Bhīṣma-Parva however appears to imply that this Parva may have been edited around the 4th century.[33]

The Ādi-Parva includes the snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) of Janamejaya, explaining its motivation, detailing why all snakes in existence were intended to be destroyed, and why despite this, there are still snakes in existence. This sarpasattra material was often considered an independent tale added to a version of the Mahābhārata by "thematic attraction" (Minkowski 1991), and considered to have a particularly close connection to Vedic (Brahmana) literature. The Pañcavimśa Brahmana (at 25.15.3) enumerates the officiant priests of a sarpasattra among whom the names Dhṛtarāṣtra and Janamejaya, two main characters of the Mahābhārata's sarpasattra, as well as Takṣaka, the name of a snake in the Mahābhārata, occur.[34]

The Suparṇākhyāna, a late Vedic period poem considered to be among the "earliest traces of epic poetry in India," is an older, shorter precursor to the expanded legend of Garuda that is included in the Āstīka Parva, within the Ādi Parva of the Mahābhārata.[35][36]

Historical references

The earliest known references to bhārata and the compound mahābhārata date to the Aṣṭādhyāyī (sutra 6.2.38)[37] of Pāṇini (fl. 4th century BCE) and the Aśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra (3.4.4). This may mean the core 24,000 verses, known as the Bhārata, as well as an early version of the extended Mahābhārata, were composed by the 4th century BCE. However, it is not certain whether Pāṇini referred to the epic, as bhārata was also used to describe other things. Albrecht Weber mentions the Rigvedic tribe of the Bharatas, where a great person might have been designated as Mahā-Bhārata. However, as Páṇini also mentions characters that play a role in the Mahābhārata, some parts of the epic may have already been known in his day. Another aspect is that Pāṇini determined the accent of mahā-bhārata. However, the Mahābhārata was not recited in Vedic accent.[38]

The Greek writer Dio Chrysostom (c. 40 – c. 120 CE) reported that Homer's poetry was being sung even in India.[39] Many scholars have taken this as evidence for the existence of a Mahābhārata at this date, whose episodes Dio or his sources identify with the story of the Iliad.[40]

Several stories within the Mahābhārata took on separate identities of their own in Classical Sanskrit literature. For instance, Abhijñānaśākuntala by the renowned Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa (c. 400 CE), believed to have lived in the era of the Gupta dynasty, is based on a story that is the precursor to the Mahābhārata. Urubhaṅga, a Sanskrit play written by Bhāsa who is believed to have lived before Kālidāsa, is based on the slaying of Duryodhana by the splitting of his thighs by Bhīma.[41]

The copper-plate inscription of the Maharaja Sharvanatha (533–534 CE) from Khoh (Satna District, Madhya Pradesh) describes the Mahābhārata as a "collection of 100,000 verses" (śata-sahasri saṃhitā).[41]

The 18 parvas or books

The Mahabharata begins with the following hymn and in fact this praise has been made at the beginning of every Parva:

"Om! Having bowed down to Narayana and Nara (Arjuna), the most exalted male being, and also to the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered."[43]

Nara-Narayana were two ancient sages who were the portion of Shree Vishnu. Nara was the previous birth of Arjuna and the friend of Narayana, while Narayana was the incarnation of Shree Vishnu and thus the previous birth of Shree Krishna.

The division into 18 parvas is as follows:

| Parva | Title | Sub-parvas | Contents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adi Parva (The Book of the Beginning) | 1–19 | How the Mahābhārata came to be narrated by Sauti to the assembled rishis at Naimisharanya, after having been recited at the sarpasattra of Janamejaya by Vaisampayana at Takṣaśilā. The history and genealogy of the Bharata and Bhrigu races are recalled, as is the birth and early life of the Kuru princes (adi means first). Adi parva describes Pandava's birth, childhood, education, marriage, struggles due to conspiracy as well as glorious achievements. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Sabha Parva (The Book of the Assembly Hall) | 20–28 | Maya Danava erects the palace and court (sabha), at Indraprastha. The Sabha Parva narrates the glorious Yudhisthira's Rajasuya sacrifice performed with the help of his brothers and Yudhisthira's rule in Shakraprastha/Indraprastha as well as the humiliation and deceit caused by conspiracy along with their own action. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Vana Parva also Aranyaka-Parva, Aranya-Parva (The Book of the Forest) | 29–44 | The twelve years of exile in the forest (aranya). The entire Parva describes their struggle and consolidation of strength. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Virata Parva (The Book of Virata) | 45–48 | The year spent incognito at the court of Virata. A single warrior (Arjuna) defeated the entire Kuru army including Karna, Bhishma, Drona, Ashwatthama, etc. and recovered the cattle of the Virata Kingdom.[44] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Udyoga Parva (The Book of the Effort) | 49–59 | Preparations for war and efforts to bring about peace between the Kaurava and the Pandava sides which eventually fail (udyoga means effort or work). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Bhishma Parva (The Book of Bhishma) | 60–64 | The first part of the great battle, with Bhishma as commander for the Kaurava and his fall on the bed of arrows. The most important aspect of Bhishma Parva is the Bhagavad Gita narrated by Krishna to Arjuna.(Includes the Bhagavad Gita in chapters 25–42.)[45][46] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Drona Parva (The Book of Drona) | 65–72 | The battle continues, with Drona as commander. This is the major book of the war. Most of the great warriors on both sides are dead by the end of this book. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Karna Parva (The Book of Karna) | 73 | The continuation of the battle with Karna as commander of the Kaurava forces. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Shalya Parva (The Book of Shalya) | 74–77 | The last day of the battle, with Shalya as commander. Also told in detail, is the pilgrimage of Balarama to the fords of the river Saraswati and the mace fight between Bhima and Duryodhana which ends the war, since Bhima kills Duryodhana by smashing him on the thighs with a mace. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Sauptika Parva (The Book of the Sleeping Warriors) | 78–80 | Ashvattama, Kripa and Kritavarma kill the remaining Pandava army in their sleep. Only seven warriors remain on the Pandava side and three on the Kaurava side. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Stri Parva (The Book of the Women) | 81–85 | Gandhari and the women (stri) of the Kauravas and Pandavas lament the dead and Gandhari cursing Krishna for the massive destruction and the extermination of the Kaurava. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Shanti Parva (The Book of Peace) | 86–88 | The crowning of YudhishthirThe Mahābhārata (/məˌhɑːˈbɑːrətə, ˌmɑːhə-/ mə-HAH-BAR-ə-tə, MAH-hə-;[1][2][3][4] Sanskrit: महाभारतम्, Mahābhāratam, pronounced [mɐɦaːˈbʱaːrɐt̪ɐm]) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India revered in Hinduism, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa.[5] It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kurukshetra War, a war of succession between two groups of princely cousins, the Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas. It also contains philosophical and devotional material, such as a discussion of the four "goals of life" or puruṣārtha (12.161). Among the principal works and stories in the Mahābhārata are the Bhagavad Gita, the story of Damayanti, the story of Shakuntala, the story of Pururava and Urvashi, the story of Savitri and Satyavan, the story of Kacha and Devayani, the story of Rishyasringa and an abbreviated version of the Rāmāyaṇa, often considered as works in their own right.  Traditionally, the authorship of the Mahābhārata is attributed to Vyāsa. There have been many attempts to unravel its historical growth and compositional layers. The bulk of the Mahābhārata was probably compiled between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century CE, with the oldest preserved parts not much older than around 400 BCE.[6][7] The text probably reached its final form by the early Gupta period (c. 4th century CE).[8][9] The Mahābhārata is the longest epic poem known and has been described as "the longest poem ever written".[10][11] Its longest version consists of over 100,000 śloka or over 200,000 individual verse lines (each shloka is a couplet), and long prose passages. At about 1.8 million words in total, the Mahābhārata is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, or about four times the length of the Rāmāyaṇa.[12][13] W. J. Johnson has compared the importance of the Mahābhārata in the context of world civilization to that of the Bible, the Quran, the works of Homer, Greek drama, or the works of William Shakespeare.[14] Within the Indian tradition it is sometimes called the fifth Veda.[15] The title is translated as "Great Bharat (India)," or "the story of the great descendents of Bharata."[16][17] Textual history and structure The epic is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyāsa, who is also a major character in the epic. Vyāsa described it as being itihāsa (transl. history). He also describes the Guru–shishya tradition, which traces all great teachers and their students of the Vedic times. The first section of the Mahābhārata states that it was Ganesha who wrote down the text to Vyasa's dictation, but this is regarded by scholars as a later interpolation to the epic and the "Critical Edition" doesn't include Ganesha at all.[18] The epic employs the story within a story structure, otherwise known as frametales, popular in many Indian religious and non-religious works. It is first recited at Takshashila by the sage Vaiśampāyana,[19][20] a disciple of Vyāsa, to the King Janamejaya who was the great-grandson of the Pāṇḍava prince Arjuna. The story is then recited again by a professional storyteller named Ugraśrava Sauti, many years later, to an assemblage of sages performing the 12-year sacrifice for the king Saunaka Kulapati in the Naimiśa Forest.  The text was described by some early 20th-century Indologists as unstructured and chaotic. Hermann Oldenberg supposed that the original poem must once have carried an immense "tragic force" but dismissed the full text as a "horrible chaos."[21] Moritz Winternitz (Geschichte der indischen Literatur 1909) considered that "only unpoetical theologists and clumsy scribes" could have lumped the parts of disparate origin into an unordered whole.[22] Accretion and redaction Research on the Mahābhārata has put an enormous effort into recognizing and dating layers within the text. Some elements of the present Mahābhārata can be traced back to Vedic times.[23] The background to the Mahābhārata suggests the origin of the epic occurs "after the very early Vedic period" and before "the first Indian 'empire' was to rise in the third century B.C." That this is "a date not too far removed from the 8th or 9th century B.C."[7][24] is likely. Mahābhārata started as an orally-transmitted tale of the charioteer bards.[25] It is generally agreed that "Unlike the Vedas, which have to be preserved letter-perfect, the epic was a popular work whose reciters would inevitably conform to changes in language and style,"[24] so the earliest 'surviving' components of this dynamic text are believed to be no older than the earliest 'external' references we have to the epic, which include an reference in Panini's 4th century BCE grammar Aṣṭādhyāyī 4:2:56.[7][24] Vishnu Sukthankar, editor of the first great critical edition of the Mahābhārata, commented: "It is useless to think of reconstructing a fluid text in an original shape, based on an archetype and a stemma codicum. What then is possible? Our objective can only be to reconstruct the oldest form of the text which it is possible to reach based on the manuscript material available."[26] That manuscript evidence is somewhat late, given its material composition and the climate of India, but it is very extensive. The Mahābhārata itself (1.1.61) distinguishes a core portion of 24,000 verses: the Bhārata proper, as opposed to additional secondary material, while the Aśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra (3.4.4) makes a similar distinction. At least three redactions of the text are commonly recognized: Jaya (Victory) with 8,800 verses attributed to Vyāsa, Bhārata with 24,000 verses as recited by Vaiśampāyana, and finally the Mahābhārata as recited by Ugraśrava Sauti with over 100,000 verses.[27][28] However, some scholars, such as John Brockington, argue that Jaya and Bharata refer to the same text, and ascribe the theory of Jaya with 8,800 verses to a misreading of a verse in Ādiparvan (1.1.81).[29] The redaction of this large body of text was carried out after formal principles, emphasizing the numbers 18[30] and 12. The addition of the latest parts may be dated by the absence of the Anuśāsana-Parva and the Virāta Parva from the "Spitzer manuscript".[31] The oldest surviving Sanskrit text dates to the Kushan Period (200 CE).[32] According to what one character says at Mbh. 1.1.50, there were three versions of the epic, beginning with Manu (1.1.27), Astika (1.3, sub-Parva 5), or Vasu (1.57), respectively. These versions would correspond to the addition of one and then another 'frame' settings of dialogues. The Vasu version would omit the frame settings and begin with the account of the birth of Vyasa. The astika version would add the sarpasattra and aśvamedha material from Brahmanical literature, introduce the name Mahābhārata, and identify Vyāsa as the work's author. The redactors of these additions were probably Pāñcarātrin scholars who according to Oberlies (1998) likely retained control over the text until its final redaction. Mention of the Huna in the Bhīṣma-Parva however appears to imply that this Parva may have been edited around the 4th century.[33]  The Ādi-Parva includes the snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) of Janamejaya, explaining its motivation, detailing why all snakes in existence were intended to be destroyed, and why despite this, there are still snakes in existence. This sarpasattra material was often considered an independent tale added to a version of the Mahābhārata by "thematic attraction" (Minkowski 1991), and considered to have a particularly close connection to Vedic (Brahmana) literature. The Pañcavimśa Brahmana (at 25.15.3) enumerates the officiant priests of a sarpasattra among whom the names Dhṛtarāṣtra and Janamejaya, two main characters of the Mahābhārata's sarpasattra, as well as Takṣaka, the name of a snake in the Mahābhārata, occur.[34] The Suparṇākhyāna, a late Vedic period poem considered to be among the "earliest traces of epic poetry in India," is an older, shorter precursor to the expanded legend of Garuda that is included in the Āstīka Parva, within the Ādi Parva of the Mahābhārata.[35][36] Historical referencesThe earliest known references to bhārata and the compound mahābhārata date to the Aṣṭādhyāyī (sutra 6.2.38)[37] of Pāṇini (fl. 4th century BCE) and the Aśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra (3.4.4). This may mean the core 24,000 verses, known as the Bhārata, as well as an early version of the extended Mahābhārata, were composed by the 4th century BCE. However, it is not certain whether Pāṇini referred to the epic, as bhārata was also used to describe other things. Albrecht Weber mentions the Rigvedic tribe of the Bharatas, where a great person might have been designated as Mahā-Bhārata. However, as Páṇini also mentions characters that play a role in the Mahābhārata, some parts of the epic may have already been known in his day. Another aspect is that Pāṇini determined the accent of mahā-bhārata. However, the Mahābhārata was not recited in Vedic accent.[38] The Greek writer Dio Chrysostom (c. 40 – c. 120 CE) reported that Homer's poetry was being sung even in India.[39] Many scholars have taken this as evidence for the existence of a Mahābhārata at this date, whose episodes Dio or his sources identify with the story of the Iliad.[40] Several stories within the Mahābhārata took on separate identities of their own in Classical Sanskrit literature. For instance, Abhijñānaśākuntala by the renowned Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa (c. 400 CE), believed to have lived in the era of the Gupta dynasty, is based on a story that is the precursor to the Mahābhārata. Urubhaṅga, a Sanskrit play written by Bhāsa who is believed to have lived before Kālidāsa, is based on the slaying of Duryodhana by the splitting of his thighs by Bhīma.[41] The copper-plate inscription of the Maharaja Sharvanatha (533–534 CE) from Khoh (Satna District, Madhya Pradesh) describes the Mahābhārata as a "collection of 100,000 verses" (śata-sahasri saṃhitā).[41] The 18 parvas or booksThe Mahabharata begins with the following hymn and in fact this praise has been made at the beginning of every Parva: "Om! Having bowed down to Narayana and Nara (Arjuna), the most exalted male being, and also to the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered."[43] Nara-Narayana were two ancient sages who were the portion of Shree Vishnu. Nara was the previous birth of Arjuna and the friend of Narayana, while Narayana was the incarnation of Shree Vishnu and thus the previous birth of Shree Krishna. The division into 18 parvas is as follows:

|

Comments

Post a Comment